The last article of mine was titled “Prospecting after Winter Storms.” There I was talking about what effect the heavy winter rains and snow had on the gold deposits in the rivers. In that exploration effort of a much smaller stream we didn’t see the redistribution of gravels that we anticipated and our plans were to move on to the larger rivers and see the effect there.

We just did that and yes, there was definite movement and redistribution of the gravels and other prospectors have seen this as well. This report to you is about what we saw and our efforts to recover some of the gold!

There are many classifications of placer deposits and for just a quick review lets cover the major ones.

Residual Placers: This is as close as you can get to the hardrock deposit of a gold bearing vein. It’s actually where the gold vein has decomposed over millions of years, disintegrating through oxidation and erosion, and basically leaving the gold on the surface and on top of the vein itself. This process could be many feet deep and extremely rich.

Eluvial deposits: This residual placer as defined above, through erosion processes, can work its way down a hillside or ravine, leaving gold basically from the top to the bottom. This deposit can cover a lot of distance, and I’ve seen it for over 400 feet. That’s a story in itself!

Marine or beach deposits: The gold sources in these deposits vary, and can come from wave action against cliffs, from off-shore currents bringing in gold bearing material from under the ocean, or even from gold bearing streams that have flowed into the beach areas eons ago.

Stream Placers: This is one of the most important sources of gold today for the prospector. These streams carry gold from eroded veins, and concentrate them in various ways. Here is a further breakdown.

- Modern day: this references our present streams that are gold bearing.

- Tertiary and intervolcanic channels: These rivers are generally buried from mud and volcanic flows and are rivers that existed prior to our modern day channels. Hydraulic pits exposed many of these flows.

- High benches: As rivers cut their way deeper into the bedrock, they sometimes leave deposits of gravel on the mountain or hillside and are not eroded away. We see them above the rivers today and in some cases over 300 feet higher than the present streams. In many cases they are cemented gravels and hard to mine without crushing.

- Desert Placers: This is similar to a river placer except that there is not a constant water flow. Generally torrential flooding is the normal water source.

- Glacial Stream deposits: The streams created by the melting glacier may serve as a normal river placer and will concentrate the gold if the water flow is sufficient.

There are other types of placers as well, and even these basically defined above have many variations, none of which I briefly covered. There are auriferous sand dunes, gold bearing alluvial fans, and even gold bearing river channels deep under the ocean. Some of these are being mined now.

All this brings us to the purpose of this article, which I’m now calling “Flood Plain Gold” deposits. This could fall under one of the above classifications called “Stream Placers.” I hear this term of flood plain gold all the time and use it myself as well, but what is it really? Where does it come from, and how can you find it? To answer this question, I’ve researched some of the best mining books, articles, and Internet searching as well. There isn’t anyone who addresses this very well and none choose to elaborate on it.

A pamphlet titled “Placer Examination” put out by the Department of the Interior Tech Bulletin 4 has a very simple explanation. To quote: “Fine-sized gold flakes carried or redistributed by flood waters and deposited on gravel bars as the flood waters recede.” It further says Float gold is “… particles of gold so small and thin that they float on and are being carried off by the water.”

I know they don’t float because of their specific gravity, but air can get under a thin, flat flake and float it away, especially when its being tumbled by high water velocities. We all have seen fine gold float in a gold pan sometimes.

To elaborate on this further. We’re talking about heavy winter storms that have the rivers roaring, sufficiently enough to turn part of the bedload over, and to move the river bar gravels from one place to another. Within these gravels are generally fine gold that has been previously deposited there.

A sluice box is a good example of this distribution. If you have a normal sluice box and dump into the apron front of it, or a dredge box, the heavier gold drops and stops at the head of the box. Many times it’s visible and hangs right there at the front. The finer gold, because of the water velocity, gets moved further down and distributed behind the riffles and caught in the matting.

Flood plain gold is similar. Heavy river flows, way up and above the normal banks, generally drops the heavier gold in the front of the bar and then, as the pressure decreases as it enters the bar, starts dropping the finer gold into the mixed gravels. Given enough time, some of this finer gold will work its way to bedrock, but generally it gets moved time and again.

The secret is to find that drop point and to capitalize on its accumulation. Fine gold looks fantastic in a pan or box, but its weight can be deceivingly light. It takes a lot of finer gold to be equal to a larger piece and to have enough weight to make the recovery effort worthwhile.

So this past month a trip to the North Fork of the American was made to search out this distribution and to see what the past winter storms did towards this concentration, if any.

I’ve spent over 40 years prospecting and mining and I’ve definitely seen my share of this fine gold. Still, the hunt is a real challenge and we never stop learning. Learned more this time too.

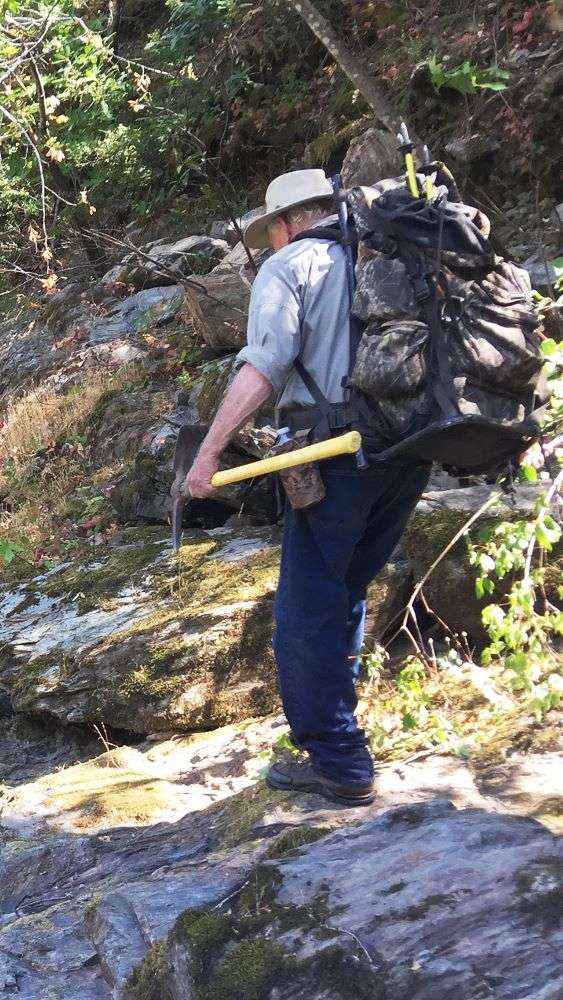

There were two of us on this search. Why is it that we never go to a place just off the road to do this prospecting? My excuse is that half the world has been there and I need to get a more remote and undisturbed area. Besides, the exercise never hurts. Cindy Hume and I were on this venture. She has been panning for years and we had a challenge ahead.

We went up the North Fork of the American and it wasn’t easy. The rivers this year still run a lot of water, much more than normal. Many creeks are still running that are normally dry. This adds more water to the rivers. We followed a trail for almost an hour before we started panning and the gold was minimal but showing color. Not enough for the effort though. To continue on up it was necessary to cross the river. Normally it’s really easy this time of year. Not at this spot this year. There were rapids just up ahead and the water was just too swift and deep to cross safely. Besides, the rocks were getting slippery this time of year. We chose a spot that looked relatively calm, compared to the rest of the flow. The river looked about three feet deep at the deepest point, which was ok. The weather was bordering on hot. Herein lies a lesson about water flows. Calm on the surface but really swift underneath, swift enough to knock you down. I had a hiking pole in one hand and a pick in the other. Cindy came across with two hiking poles. These poles kept our stability and served as a brace against the swiftness of the water. We could not have crossed without them. The undercurrent would have taken a person down.

Once over we hiked on up the river and crossed again, finally to a small river bar along a bedrock wall. Across and up stream of this bar was a 30 foot high wall of river gravel from an old bench deposit that the old time miners chose not to work. Maybe the gold was too fine.

Bedrock didn’t show on the floor of the bar but lots of old grass roots were there. It was hard digging but the first and every pan thereafter had color. A few pans had lots of fine gold showing and a couple of times there were several decent flakes. These grass roots on the bottom of the gravel floor were catching the flour gold, just like the matting in a sluice box. The color was hard to leave because it was giving gold every time.

You know how it is just around the next curve? Don’t we always have to go and check? Absolutely. 200 yards away was the final stop of the day and this time the flour gold was even better. It was primarily hanging up in some old grass roots again. The problem was we had just gold pans and not a sluice box. Even with a box it would have been hard. The potential setup was maybe 50 yards away. That meant a long carry every time.

I bet you all have seen this many times. The gold you are digging is way off from the setup of a box. I think that’s because we are in the drop zone of gold, where the water velocity lets up. Likely the river is broader there and slower, making it hard for the sluice box to have enough water grade for it to work properly. A power sluice is a good alternative, where you can pump water up to the box on the bank. There are numerous restrictions by Fish and game on this setup, but barring that, it’s necessary to carry that setup with you. That’s not good for long distances.

Where we were on this prospecting trip was in the Wild River classification system where motorized equipment is illegal.

By the end of the day we had to leave. It was a two-hour hike out and we did not want to be hiking in the dark. The final gold recovery was 1.3 pennyweight. It looked like more weight than that, but it takes a lot of fine gold to equal one pennyweight. Considering we were only panning, this was pretty good for flood plain gold!

Next time we’re going for bedrock crevices. Flour gold is good but greed sets in and better gold can be had….it says in fine print.

Until the next time.