In 1717 Sir Isaac Newton, Master of the British Mint, established a fixed price for gold. This price was for bullion gold, refined to a purity of twenty-two carats (.917 fine). This fineness meant that 917 of 1000 parts was pure gold, therefore leaving 83/1000 as impurities. (Today the bullion gold bars are .995 fine, and in some cases .999 fine). This price remained the same for over 200 years, until February 1934 when President Roosevelt set the price of gold at $35.00 per ounce as part of his “Gold Reserve Act” which dealt with the great depression.

So why the great importance of the metal “gold” and what did it mean to our country? Part of this answer starts with our U.S. Constitution, Article I, Section 10, 1. titled “Powers Prohibited, “Absolutely no state shall…make anything but gold and silver coin in payment of debts.” The year was 1787, well over 60 years before the gold rush started.”

At that time, the U.S. Government had already had a bad taste of paper money when, in January, 1777, six months after our Nations independence, the Continental Congress requested that the thirteen states declare the first paper money “Continental bills” legal tender currency. This was ratified with the agreement that the Continental dollar be equally exchanged for gold and silver coins of the same value. In theory it sounded fine, but as more and more bills were printed, the value against the gold decreased. By 1780, only three years later, the continental dollar had dropped in value to the point that it took 400 Continental dollars to buy one dollar of gold or silver! This paper money failure brought on the expression “Not worth a Continental.”

This experience with paper money about seven years before the Constitution was ratified was definitely a determining factor in the writing of Article I, Section 10. I’m not a legal scholar, but my understanding is that this section of the Constitution has not been amended The California gold rush starting in 1849 was perfect timing in that the U.S. was on a gold standard and finding gold was absolutely the same as finding money – sort of. It just needed refining and a conversion process into gold coins. Many of the California mines were in full swing, particularly the hydraulic operations and gold was plentiful. The miners needed to sell their gold and the newly opened U.S. Mint in San Francisco was a perfect market, paying $16.00 per ounce to any seller who walked in the door.

This created the middleman who was the go-between for the miner and the mint. Many miners did not have the time or inclination to travel to San Francisco, recognizing the lost time and cost involved. It was worth it to sell the gold to the local buyer for $15.00 per ounce, since the $1.00 loss per ounce was insignificant when compared to the cost of the long travel to the coast. Sometimes Wells Fargo served in this middle man role, by buying directly from the miner and then delivering and selling the gold to the mint. One major potential problem – stage robberies, particularly by Black Bart, who had been terrorizing their stages for several years (See Foresthill Messenger April 16, 1999, Sesquicentennial Chronicle Section titled “Black Bart”).

The San Francisco U.S. Mint officially opened its doors in 1854, and produced four million dollars in gold coins the first year. By 1856 this figure had gone to $24 million dollars in gold and silver. The Mint produced five basic gold coins. These were the $20.00 Double Eagle (one ounce of gold); the $10.00 Eagle (1/2 ounce); the $5.00 Half-eagle; the $3.00 gold piece; and the $2.50 Quarter Eagle.

Actually, even though the gold content is generally listed as indicated, technically there is a variance. Because gold is soft and will therefore wear quickly, the Mint added 10 percent copper to each of the coins. This hardened it up but also changed the weight. For example, the standard twenty-dollar gold coin (1850 – 1933) weighed 33.4 grams, whereas a troy ounce of gold weighs 31.1 grams. This additional weight was copper, with one clarification….the Mint actually only placed .96750 ounces of pure gold in the coin. All this means the gold coins didn’t have quite the amount of gold that the general public thought, and the weight was a little heavier because of the copper addition.

Today these gold coins are worth anywhere from three times the gold content value, to prices ranging up to thousands of dollars for uncirculated specimens.

All this means you better check out any old trunks that have been passed down over the years because you never know what values might just be lurching inside! Treasure hunters, in searching old homesites, have found gold coins inside old walls, under floorboards, and in just about every hiding place imaginable. Metal Detectors, which now discriminate for gold, have become a major tool in searching for these lost treasures.

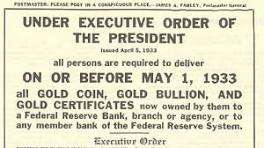

So why are the coins so expensive and so hard to find? Ask our U.S. Government where they are. After all, they collected them, by law, from every person in this country, under threat of fines and imprisonment. Sound strange? Let’s go back to March 6, 1933…

Remember that our country was on the gold standard, meaning that all paper money was 100% backed by the U.S. Government. Early in 1933 a banking panic sent depositors flocking to withdraw their accounts in gold, fearing that the paper money was in jeopardy of failure. Franklin D. Roosevelt, in stemming the tide, closed all the U.S. Banks from March 6-9, 1933, and instituted a proclamation that declared:

- An embargo on the withdrawal of gold and silver.

- A requirement that everyone turn in all gold and silver. Failure to do so would result in a fine of $10,000 and a prison term of 10 years.

- An authorization for the Secretary of the Treasury to make regulations for banking control.

- As a result of this proclamation, a tidal wave of gold poured into the vaults of the twelve Federal Reserve banks. The Newsweek magazine of March 11, 1933, seems to have stated it best:

- “It was a new lesson in mass psychology. Day after day, in growing numbers, men and women formed long lines before bank windows, in their rush to escape the stigma and the threatening penalties for holding gold. Banks added extra guards and extra tellers, opened their doors early and kept them open late. By Saturday, last week, a veritable stampede had developed to get rid of the gold.

- By foot and motor the depositors came, with briefcases, satchels, paper parcels, little bundles and bulging pockets. Some only had $5.00 gold pieces saved from Christmas. Others lugged boxes of “double eagles” totaling several thousand dollars. All filled out deposit slips, watched tellers check off their names, and hurried out again. Many asked questions, protested they were not hoarders, transacted their business speedily, took currency for their gold deposits, and left with evident relief.

- Locksmiths in the nation did a rushing business, to their surprise and gratification. They picked locks of dusty wall safes with forgotten combinations, of cobwebbed trunks and tin boxes for which there were no keys. They called in detectives for some of the larger jobs, to have protection on their unaccustomed tasks.”

- Fears became worse when it was stated that the “Feds” had lists of those people who, in previous years, had exchanged paper money for gold, and they were now checking the names on those lists against those who brought gold back in. The “Ban” was on, and the rest of the world watched as the government of the freest people on earth forced its citizens to hand over $570 million in gold, for $570 million in paper money. This process went on for ten months.

- Once this gold was secured, in 1934, Roosevelt passes the “Gold Reserve Act.” This provided:

- For the immediate nationalization of the country’s gold reserves.

- Put the nation on a gold bullion standard but prohibited gold coinage or gold redemption of paper money.

- Gave the Secretary of the Treasury new monetary and financial powers.

This entire process took two years and gave the government the physical possession of the gold, control of gold exports, and a way to fix the price of gold. Then the U.S. raised the price of gold from $20.67 to $35.00 per ounce. What a profit it made on the reserves! It brought the gold from the citizens for $20.67 per ounce, and then increased its value to $35.00 per ounce.

We must keep in mind the wisdom of Roosevelt. The history of our country to that point had shown that when paper money was issued, while gold was still in the market place and being used, the paper money failed – and generally because of its competition with gold. By removing all gold there was no competition. The paper money was the only money, and therefore would be acceptable under all other conditions.

The dollar was then backed by 40% gold, rather than the previous 100% backing. This set a world value and held until 1945, when the gold backing for the dollar was reduced to 25%. This was changed to 18% in the 1960’s, and in 1968 the gold backing was removed from U.S. currency. On August 1, 1971, Richard Nixon announced to the world that the U.S. would no longer redeem gold for dollars.

All of this history is interesting, but back to the discussion about why gold coins are so expensive. Next month’s blog will discuss further the U.S. Mint and how the gold from these coins likely got into the French vaults; how the U.S. lost much of its gold reserves; and why the government no longer has the historic coins that were turned in by the people. These three major factors will provide the answers about supply and demand for these historic coins.

Bibliography: The Constitution of the United States of America and the Constitution of the State of California, California Sesquicentennial 1849-1999 Edition, Published by the California State Senate ( ID 99 03256-100); The New World of Gold, Timothy Green, Walker and Company, New York, New York. 1981; The War on Gold, by Antony Sutton, “76 Press” 1977; Fabulous Gold, Publishers House, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1975; History of Money, Dr. Leroy Brenna, cassette tapes, Texas, 1983; A Guide Book of United States Coins, R.S. Yeoman, St. Martin’s Press, New York, New York, 2000.