Yankee Jim’s was booming, with hydraulic mining dominating the scene at Georgia Hill, at Oliver Wendell Henderson’s hydraulic pit, and at Yankee Gulch. We covered this in the last month’s article and the difficulties were monumental. If two words had to describe the miners of that time I would choose persistence and determination. If you want to put together the total package, add to that a mixture of hope, expectations, and the potential of a substantial living, blend it all together, and you would have our 49er.

This breed of men didn’t wait for a detailed map on where to go. They had their ear to the grapevine, and it didn’t take long for the information about Yankee Jim’s to travel to San Francisco and to all points south. Miner’s and want-to-be miners hitched up their mules, loaded them down with equipment and supplies, and struck out for points north and east. Of course, having mules was a luxury that few could afford. Many simply walked and worked their way, carrying a backpack with their gold pan, digging tools, and a huge supply of hope.

This was 1852, and the gold rush was booming. P.T. Barnum, back east, was already promoting Jenny Lind, the Swedish Nightingale brought all the way from Europe for a whirlwind tour of the great United States. This was the first such tour ever taken by a European celebrity, and according to historians, still remains as the most spectacular and successful of them all for the 19th century. When she arrived in New York in September of 1850 thirty thousand people greeted her and the demand for her concerts and shows was unprecedented for the times. The tickets for her first performances were sold at public auction rather than the box office. The demand was astronomical. The first ticket alone went for $625.00, and a young poet and college professor, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, could only muster a bid of $8.00, which got him a seat in the gallery.

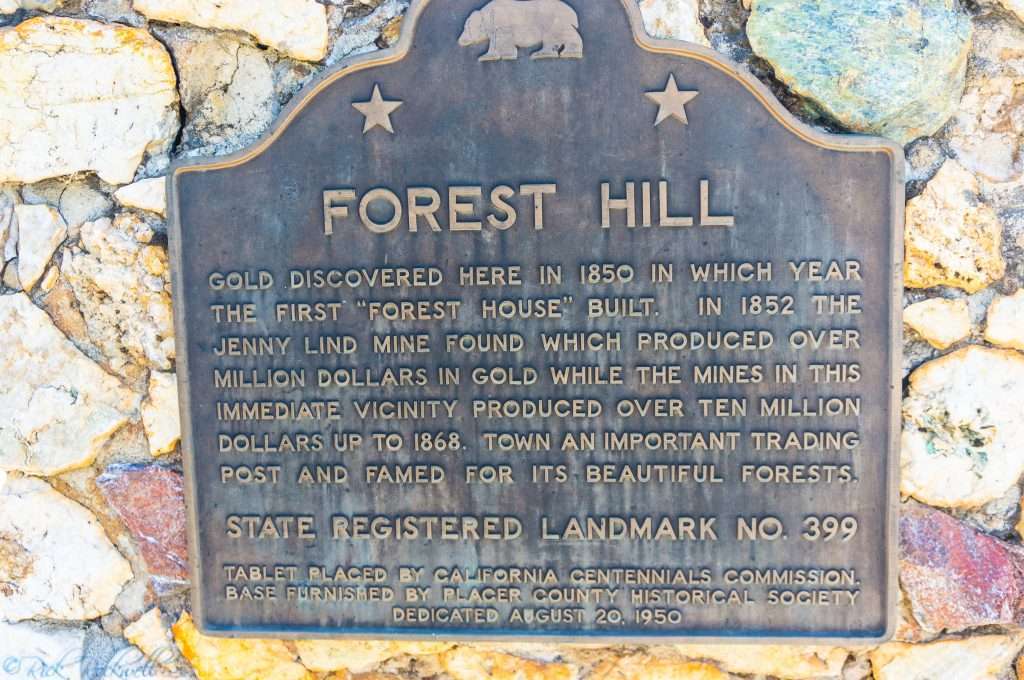

Jenny Lind rapidly became a legend and P.T. Barnum perhaps became the greatest showman of them all. He saw the enormous opportunity of the golden West, and Jenny Lind soon migrated to meet the miners. In 1852, her name had already made its way close to Yankee Jim’s, because, just east of town, down below the Forest House which had just been set up as a trading post, was a ravine called the Jenny Lind Canyon. This was to become the site of the Jenny Lind Mine, one of the best paying drift mines in California, but that’s getting ahead of our story.

The Jenny Lind Ravine was being worked heavily by ground sluicing, some hydraulicing, and just plain sluice box work. The gravels were paying well but the originating source had not been located. The claim belonged to Snyder, Brown and Company, and they worked diligently up until December of 1852, when heavy rains drove them out of the wash. The storm extended almost continually for two months, and finally subsided in early February of 1853. Hugh volumes of water rushed down the ravine and the miners watched helplessly as equipment and their diggings vanished in tons of mud and overburden. When it was all over despair was the word. Two years of work had vanished. Their tools were either buried or washed down the canyon and all the bedrock exposure and crevices they had developed were lost.

The scene was likely what we see when disaster occurs somewhere in our country, as fire, earthquakes, and tornados destroy homes and towns. In these situations people appear absolutely lost as they wander around, kicking debris out of the way, looking for some evidence of their previous activities and belongings – and that was what the miners were doing.

From their viewpoint it was a lost cause with years of work gone, and yet…. as they walked around surveying the scene and the damage, Mother Nature decided to play a hand and reward them for their hard work. During the two earlier years of their mining, they had removed thousands of yards of material. This created a void area, and when the pressure of the flooding waters moved other gravels to replace the void, a domino effect was created. Each void was filled by new material from higher up the ravine, and finally a slide occurred along the side of the ravine, and this slide exposed ancient river gravels in place.

Down below this point the miners were astonished to find large pieces of gold intermixed in the overburden. What appeared to be a disaster turned the corner to become a bonanza. The miners began working feverishly at the new prospect, working their way up the ravine to finally encounter the source of the gold that they had been mining for years. The new prospect was paying handsomely, as it was described in those days, with $2,000 to $3,000 dollars of gold per day being washed. (Remember that today’s values would place this at $36,000 to $54,000 per day!) They had struck it rich, and tunnel work began very soon thereafter. The Jenny Lind Mine was on its way to become one of the richest mines on the Divide.

Nearby, Phillip Deidesheimer was already driving a drift tunnel into part of the ancient channel that some were calling the Blue Lead. He was a mining engineer from Germany, initially having worked down south in the Mother Lode vein system, and migrating northward as he heard about Yankee Jim’s and the potential of buried river channels. He discovered the Fair View Garden Deposit, and began his mining. Although the ground was partially cemented, heavy timbering was required, and being an engineer, he developed the first stages of a unique mining timber structure that was later to make him famous throughout the State of Nevada and the western United Sates. He mined successfully for many years and with the mine named appropriately “The Deidesheimer Mine.”

His experience with the troublesome underground mining of the Deidesheimer taught him the complexities of ground control and when he went to the Comstock Mines in Nevada he solved their most complex problem…how to prevent the footwalls and hanging walls of their vein structure from crushing their timbers and halting their mining operations. He designed the “square set” timbering method which locked itself into place, and for the first time the Comstock miners could safely mine out the rich silver ore. His timbering method spread to Montana and South Dakota and became the standard for timbering and stoping out hard rock vein systems. Not bad for a miner from Foresthill!

Other mines were springing up all around the Foresthill area in 1852 and the mining business was bursting at the seams. This was not a picnic though, and with all the successes, there were ten times as many failures. Working conditions were harsh, working wages very low, prices for goods high, and medical attention almost non-existent. Winter work outside and underground brought on pneumonia, and this deadly illness ended the career of many hard working miners.

Not everyone had jobs, and many of the men who tried prospecting were not skilled enough to make a living from it. Even though the picture was promising, and the potential for making a strike was always there, men had to survive, and many didn’t. This was not the territory for the weak hearted, and the physical stamina requirements were high.

Even with the difficulties, the community flourished and I, for one, take my hat off to the men and women of those days who most likely would laugh at what I sometimes consider a struggle! Our pioneers were strong, and they were the backbone of our history. Let’s hope we can carry forward their ideals, drive, and perseverance!